Director (Film)

Career Overview

Directors are the storytellers in charge of every creative aspect from development to post-production. They ensure that the film’s story is conveyed through the performances of the Actors, other onscreen visuals, and the overall sound design of the production.

Alternate Titles

Film Director, Movie Director

Salary Range

$250K to $2M

How To Become a Director (Film)

People also ask

- What does a Film Director do?

- What degree do Film Directors need?

- How does a director decide if they’re going to shoot their movie in color or black and white?

- What is a Film Director’s salary?

- Who is a famous Film Director?

- How do you balance staying true to your artistic vision while also meeting the expectations and demands of producers, studios, or other stakeholders?

Career Description

Film and TV Directors are some of the most respected individuals in the industry. To learn what it takes to build a successful career as a Director, we talked to several professionals working in feature films, scripted television, and reality TV.

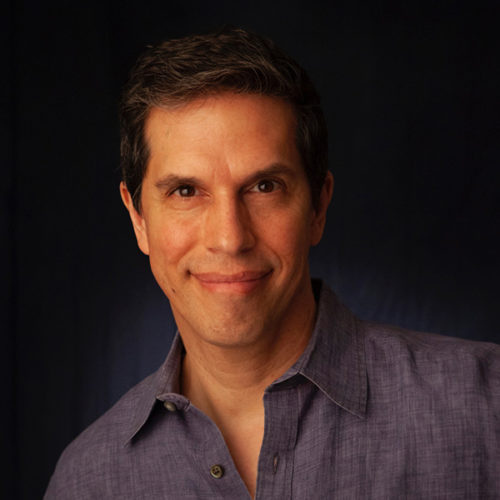

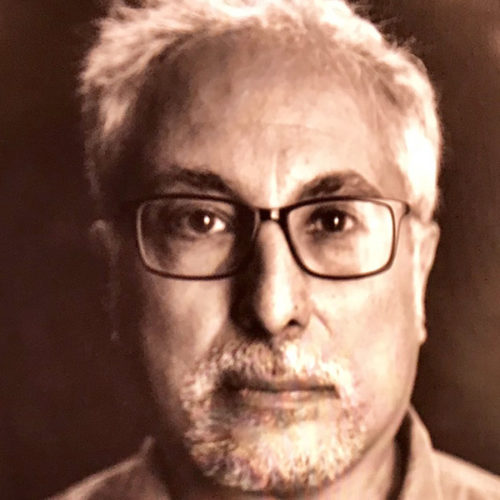

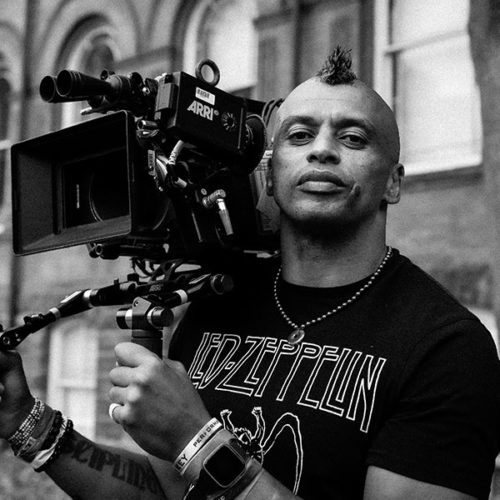

In this article, you’ll hear from:

- Hisham Abed (Queer Eye, Encore!, Siesta Key)

- Norberto Barba (Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, FBI, Mayans M.C.)

- Cassius Corrigan (Huracán, The Caregiver, Cartel)

- Bola Ogun (The Witcher, Shadow and Bone, Raising Dion)

- Mark Tonderai (Locke & Key, Spell, Impulse)

The Director is commonly thought of as the person who works with the Actors and directs their performances. However, the person in this role often has a hand in nearly every part of the filmmaking process.

Development

A Director may get hired after a film gets the green light to go into production. In many cases, though, they are part of the filmmaking process from the very beginning, which means the development phase.

They themselves may be the Screenwriter on a project or collaborate with that person to get the script to a place where studios, production companies, and financiers want to back it.

Pre-production

Whether or not a Film Director becomes attached to a project during the development phase, once it moves into pre-production, their responsibilities quickly ramp up.

The script rewriting process is likely to continue for the Director with the Screenwriter or on their own until production begins.

Pre-production is also when the Director participates in the hiring of other key crew, including the Storyboard Artist, Cinematographer, Production Designer, and Head Costume Designer, and aligns them with their intended creative vision for the film.

The Director will likewise work with the Casting Director and their Associates during the casting phase of pre-production and give the final say as to who is chosen for a given role.

Regardless of the scope of a film, the Director must communicate and collaborate with many other individuals on a film and have a working knowledge of each primary part of making a movie. This essential skill is required not only at the outset of a project but also throughout the filmmaking process.

What does a Film Director actually do? This video explains.

Principal Photography

Once principal photography begins, a significant part of the day-to-day duties of a Film Director generally involves working with the aforementioned Cinematographer, Production Designer, and Head Costume Designer, as well as the Producer(s) of the production.

Other key figures with whom the Director will typically work with on a production are the Key Grip, Gaffer, and Production Sound Mixer.

And as mentioned, a central part of the Director’s set of responsibilities during principal photography is getting great performances from their Actors and Actresses.

Post-production

When post-production begins, the job of a Director is often not done.

Many Directors are heavily involved in the process of putting together the final film, TV show, or other project. The Director will generally work closely with the Editor of the film, as well as the Re-recording Mixer, Sound Designer, Colorist, and Composer to guide the final look and sound of the project.

If a project includes visual effects, the Director will also work with the Visual Effects Supervisor to ensure that those effects are created and implemented as needed.

What does a Film Director do?

A Film Director wears many hats over the course of a production. Though they are primarily known to instruct the performances of their Actors, Directors also edit scripts, collaborate with other key crew members such as the Cinematographer and Editor, and lead the overall creative vision for their movies.

What does a Director do?

A Director interprets a script and helps assemble the crew of people that s/he communicates his/her vision to in order for the crew to help execute that “vision,” or interpretation, of the story.

Before filming starts, a period called pre-production, the Director is part of casting the roles (though not always, there are exceptions, like in TV series), “scouting” or choosing locations, deciding on the “look” or “texture” and “tone” of the film — will it be dark, light, scary, genre-specific, etc.?

During filming, or “production”, the Director gives “direction” to not only the Actors (are they interpreting and acting the scene as the Director sees it?) but also to all the other departments that contribute to the visualization of the film, including the Art Department, the Cinematographer (figure out all the shots and angles that “cover” or comprise a scene), the Costume or Wardrobe Department, Hair and Make-up Artists, etc.

One of the most important aspects of the Director’s job is to capture all the necessary pieces–the shots and scenes on time and on budget — that come together in order to edit the movie in “post-production.”

Films are shot out of order, due to practicality, so the Director has to have a clear idea of all the emotional and visual arcs that s/he envisions at any given time so that when the movie is edited, the audience is unaware of that process and sees it all as one continuous story.

Finally, visual effects, sound effects, and music are added to complete the project. All under the supervision of the Director and in collaboration with the Producers and other members of the team.

What goes into being a Director of a feature film? It starts with the screenplay. If you didn’t write the screenplay, you have to deeply, deeply understand what it is, the story that you’re telling, and why it’s going to resonate with people.

What are the critical aspects of it that just need to come across in the experience of the movie? [It’s] understanding if you can or can’t deliver those, and what you need to make sure they come across.

Take Huracán, for example. If I hadn’t written the screenplay, but I wanted to direct it, I would look at it and say, “Okay, what are the most salient things that I need to get across?”

The first thing is you really want to build the mystery and the suspense of this deep dive into severe mental illness, and I wanted to find creative, cinematic ways to put that on screen because I think that can be very thought-provoking.

That’s a huge feature of the movie. Directorially, you have to identify that type of feature, and have an idea, practically, how you’re going to bring it to life. On the other side, it was the MMA element. We had this opportunity to have this really authentic and visceral mixed martial arts fight action onscreen.

Identifying those two features of the movie as big cinematic elements that I could use and combine to create a really engaging film experience: I’d say that is kind of the most important early work as a Director, creatively.

Then, it’s working with the Producer. The better you can cast and crew up your film, the much better position you’re going to put yourself and the project in. Because even [with] myself writing, directing, lead producing, lead acting, and co-editing, there were so many other people that had to play a very big role and execute at a very high level for the movie to turn out how it did.

So, it’s really understanding what you need from your collaborators and what they want — and making sure you’re delivering that and staying conscious of that. That’s a huge part of the direction of one of these sorts of ultra-low-budget first features.

As a Director, your job is to tell the story. Which sounds super basic, but I think a lot of people are confused about what “story” is sometimes. They’re always focused on the flashier things like car chases or fight punches, but sometimes it’s just about the themes of the story; what are you trying to say?

So much can happen on set, in pre-production, and in post-production. Your job as a Director is to make sure that throughout that process, the message comes through clearly. Every decision you make–down to color, hair, makeup, the way you shoot something–is a tool to help tell the story.

Prior to COVID, my job was very simple. It’s to make everybody else their best selves. That’s still the same post-COVID, but it’s a little different.

To help everybody be their best selves means creating an environment where people feel free to create, feel free to talk about ideas, and feel free to smile without any form of recriminations. That’s really all my job is if I’m honest with you: to make everyone their best selves by creating an environment where people feel they can flourish. (That seems quite simple, but it’s not because it sort of splits into substratum.)

That involves a huge amount of preparation because crews need to know you know what you’re doing, and so do cast. Cast needs to have that trust in you, so they need to know that you know subtextually what’s going on in the text.

I’m doing a show at the moment for Netflix. I have a Showrunner that I have to answer to. I have a network, Netflix, that I have to answer to. If I’m doing a film, I have a studio that I have to answer to. So you have to take all of those into consideration, and try to keep the eye on the prize, i.e., the true north star of the story. I know that sounds a bit nebulous but that’s kind of what I do.

There are so many aspects to the Director’s job and one can answer differently depending on how one views a Director’s responsibilities. My feeling is a Director tells a story, and the Director is a leader who works and collaborates with other artists; for example, the Cinematographer, Production Designer, Casting Director. He or she works with them to tell a story.

The Director’s responsibility is to harness all that talent to tell the best story he can tell. A Director’s other main responsibility, I think, is working with Actors and getting the best performance—the truest and most honest performance.

I had a mentor once who said that the Director’s main responsibility is to separate the machinery of making film from the Actor so that the Actor can be in the moment. On a set, there’s 150 people around, there’s lights, there’s all this stuff that can distract an Actor, and the Director is there to make that disappear, to instill trust and to protect the Actor so that the Actor can be in that moment.

That’s a big responsibility. I recall Sidney Lumet, a famous Director, once said, “A Director’s most important power is when that person says, ‘Okay, print! Moving on.’” Because that means you’ve committed that you have it, now we’re moving on, you can’t go back. That’s a very important responsibility.

Salary

As with most specialties, a Director’s salary can vary wildly from one medium to another, as well as from project to project.

Let’s first discuss projects such as student films, short films, and ultra-low-budget films. In most cases, these types of projects are nonunion productions, which means that the salary is typically quite modest.

However, if we’re talking about union feature films – even those with a lower budget – the Director on it can potentially earn between $250,000 to $2 million. This wide range is dependent upon factors such as the production’s overall budget and the experience of the Director.

Learn from the best… Quentin Tarantino breaks down how to direct movies.

In addition, these figures typically correlate with a Director being part of the DGA – the Directors Guild of America – that sets rates for its members. Currently, the weekly rate for a high-budget film is $22,853 and $16,321 for a short or documentary.

In television, a Director in the DGA can earn a minimum of $31,387 per episode for a half-hour network (ABC, CBS, Fox, NBC) show. That rate can increase for a longer show but can also be significantly lower for programs that air on cable or streaming.

If a Director is not yet part of the DGA, their salary again can be significantly lower. Moreover, a Director may have substantial breaks between projects, which may mean that they only get paid for only one or two projects in a given year.

What is a Film Director’s salary?

A Film Director’s salary can vary wildly depending on the project. For mainstream projects backed by a major production company or studio, a Film Director may earn a salary between $250,000 and $2 million. However, the salaries of most Directors are far less, especially when they are working on short or independent projects. In some cases, a Film Director may negotiate backend payment from gross box office revenue if the production team is confident that it will perform well in theaters, streaming, or video on demand.

How much does a Director make?

Salaries for Directors vary as widely as the projects that they work on and even what niche of filmmaking they work in. Some projects have the base salaries regulated by the Directors Guild of America, or DGA, and can be negotiated beyond that.

A starting salary for a Reality TV Director might be $4,000 to $5,000 per week, but a Sitcom TV Director might make $60K or more per week or episode. A Commercial Director might make $40-$50K per day for a very high-end commercial, or a couple thousand dollars for a local TV commercial. Plus, there are often royalties or “residuals” you might collect (depending on the deal you’ve made) for your work after it airs or is in theaters for a period of time.

Here is a link to the DGA’s rate cards for the next year.

It depends on what path you take. For example, if you go and make an independent movie, you probably will lose money. Because you’re really putting yourself out there and you’re probably begging and borrowing to make that movie. But then ultimately, if it’s good, people will come to you and give you an opportunity to do another movie. How big the movie is kind of dictates how much you would make on it.

Television directing, it depends. There’s half-hour comedies, there’s one-hour dramas, and there’s TV movies. It could be extremely lucrative. For example, with the DGA (the Directors Guild), a one-hour drama minimum, I think is something like $47,000 for a one-hour episode. Then, you get residuals, where every time they show it, you’ll get a piece of that.

You make a great living being a Director if you’re successful, but getting there is tough, and staying there is tougher.

This is a little harder because it isn’t like most industries where, if you’re talented and hard-working, you can find a path up the ladder. There are a lot of people who are hard-working and talented in this industry who don’t get anywhere.

My theory behind that is that this business is four parts: talent, hard work, who you know, and luck. Now the percentages of those things are different. To me, luck is only 10%, and the other three are the larger percentages. You have to tackle it from all four sides, or really, three sides; the fourth side, luck, you don’t have any control over. But if you’ve done your work on the other three, it’s easier to get that 10%.

It’s tough. I’ve lived in L.A. for fifteen years, and I didn’t really start making money as a Director until last year. So it’s a long road. One of the best things you can do is, instead of focusing on how to live off of being a Director, focus on keeping your overhead low enough so you don’t have to worry about that yet. Keep your lifestyle as minimal as possible so that all your money, all your time and energy goes into what you wanna do: direct, create, and be a filmmaker.

It’s gonna be hard. It’s not gonna be comfortable. It’s annoying because everybody else is gonna have nice new cars, and you’re gonna wish you had that nice new car. But you’re focused on something bigger than the material things.

When you get those moments of struggle, or when someone who doesn’t understand your business is confused as to why you’re trying so hard for something that doesn’t give back the work you put in, tell them: the core of what you’re doing is about sending messages through your art. That’s way more important than the material things.

And hopefully, your focus will bring heat your way. People in this business are heat-seekers. It’s some of the best advice I ever received. People are heat-seekers, and unless you’re generating your own heat, no one is gonna come around and feel for you.

What creates heat is a focus on story. Focus on why you’re telling the story. Focus on what you wanna say because that’s unique to you–not everybody has what you have to say. So that’s gonna be interesting. The more you stay focused on that, the more likely you are to generate your own heat.

How do Film Directors get paid?

In many cases, Film Directors are paid a flat fee for their work on a project. However, depending on the circumstances of a production, they may negotiate for other or additional income. For instance, a Film Director who works on an ultra-low-budget movie with great potential may defer an upfront payment and opt instead for a percentage of that film’s profits.

Alternately, a Film Director who works on an expected blockbuster or known film franchise might negotiate to receive a percentage of merchandise or physical media sales in addition to their salary. It all depends on each individual circumstance, what the Producers can negotiate, and what the Director is willing to accept.

Hey, what do you think about trying our new Film Career HelperFilm Career Helper really quick? It’s totally free and could help get your career moving fast! Give it a try. It’s totally free and you have nothing to lose.

Career Outlook

The common desire to be a Film Director makes it a highly competitive field.

Unless a Director takes it upon themselves to produce a film, they’re likely vying for a limited number of opportunities along with hundreds of other creatives with similar experience and expertise.

With a greater focus on providing opportunities for individuals who historically have had a more difficult time breaking into the directing world, namely women and people of color, several programs have been created over the last few years to help aspiring Directors.

If someone was to ask who the Director in relation to the rest of the crew, how would you answer? This video describes this crew position.

Some of these programs include the AFI DWW+ and NewFest’s Black Filmmakers Initiative.

Aspiring Film Directors may also find success outside of cinema. Those looking to direct may want to consider alternate fields like TV or commercial directing. While still competitive fields to enter, they can overall provide more opportunities for Directors.

Is Film Director a good career?

If you feel drawn to tell stories through a visual medium like film, being a Film Director might be the perfect career for you. Keep in mind, though, that it is often a career with very little financial or professional stability. Some Directors like Steven Spielberg or Martin Scorsese have as much security as one can ask for, but in most cases, Directors are hustling for that next gig for their entire careers. That being said, directing as a career can afford you the opportunity to be highly creative, and should your name become a recognizable one, financially secure.

Is it hard to become a Director?

Hard depends on how you define it. The act of going out and directing something like a short film isn’t necessarily difficult. All you need is a smartphone and probably some friends to help both in front of and behind the camera. Is it hard to be a good Director? Sure, but with time, patience, and practice, you can likely pick up most or all of the skills that successful Directors have like having a clear vision, being able to collaborate with others, and of course directing your Actors to great performances.

Is it hard to be a Director with professional stability and financial security? Yes, very. Many filmmaking specialties come with high competition among both established and newcomer professionals looking to make it big, and directing is no exception. Many Directors do find success by branching out from a focus solely on directing studio-backed feature films by taking work as a music video, commercial, or other type of Director. Though not an easy career to navigate, it still draws in many people on account of the creativity and exposure it can provide.

How does a director decide if they’re going to shoot their movie in color or black and white?

While the majority of motion pictures are shot in color, there are a number of modern successful black and white films as well. The decision of which format to use is entirely stylistic and creative, as each offers its own unique impact and charm. Color film tends to add a vibrancy and dynamism to movies while black and white offers more of a nostalgic allure and classic elegance.

Several very successful films actually use a combination of formats to achieve their narrative and emotional goals. Let’s take a look at a few of them…

- Pleasantville

- Memento

- JFK

- Schindler’s List

Gary Ross’ PLEASANTVILLE, which tells the story of a brother and sister who get teleported into the black and white world of a 1950s sitcom, uses a mix of color and black and white as a key to the fabric of the film. As the 1950s grows from rigid and repressed to liberated and vibrant, so too does the film itself. Take a look at this montage, which showcases the cinematic device in action.

Christopher Nolan’s noirish psychological thriller that’s narratively told in reverse uses black and white film to establish a sense of time for the audience. The clever effect is spellbinding and requires multiple viewings to fully understand the film’s overall impact.

Oliver Stone’s JFK is a tour de force of filmmaking as the director shifts in and out of styles and formats to attempt to solve the riddle behind President Kennedy’s assassination. Switching between color and black and white gives the audience a sense of different perspectives and clarity amidst an onrush of information.

Watch this scene, where lead investigator Jim Garrison (Kevin Costner) meets with a man named X (Donald Sutherland) for a download on the labyrinthine details behind the shooting.

Steven Spielberg’s masterpiece, which tells the story of a Nazi businessman who turned his business into a haven to save Jewish lives during World War II is chiefly told in black and white. There are a few sequences in the film that infuse color, but the most memorable is the liquidation of the ghetto scene. A young girl in red catches Oskar Schindler’s eye as she moves through the horror and violence. The symbolism of the scene – how could the world not see what was happening – is chilling and the orchestration of the moment, from both a narrative and a technical angle, is flawless.

Career Path

The career path to directing can be just as individualized as the person seeking it.

Film schools across the globe offer directing tracks for students, which may be the starting point for many aspiring Directors. But as with any other aspect of the film industry, forging a successful career path often depends on the relationships formed along the way.

Aspiring Directors must learn to find connections within the film industry, which can greatly help in getting jobs all the way from a student film to a studio blockbuster. It’s also important to reach out for opportunities early in one’s career, as there’s no substitute for on-set experience.

In the vast majority of instances, a Director will not be hired to helm their first feature film unless they have experience in other mediums, such as short films, commercials, or music videos. Working outside of film to build a portfolio of work is extremely common.

If an aspiring Director isn’t finding the opportunities to gain experience through their connections, they may want to produce a project themselves. Many Directors write, direct, and produce shorts that help them demonstrate their skills to others and leverage that work for more substantial jobs.

Do you aspire to be like Spielberg, Scorsese, or Nolan? Listen to the latter talk about his experiences directing movies.

Emerging Directors can also look to any number of mentorship programs in the entertainment industry to aid their professional efforts. The DGA offers a Directors Development Initiative that pairs TV Directors with their more veteran colleagues to help expand their careers.

Other programs include the Apple Studios Directors Program, Disney Entertainment Content Directing Program, NBCU Launch Directors Program | Female Forward, Paramount Directing Initiative, Sony Pictures Television Diverse Directors Program, and Warner Bros. Discovery Access Directors Program. Each of these programs affords aspiring Directors – especially BIPOC and women Directors – the chance to further develop their skillsets.

How do you become a Film Director?

Great question. The simplest answer is you just need to start. Given that so many people have easy accessibility to smartphones, which happen to have great video production value, you can start directing your first film now. A Director is a discipline where examples of your work really matter, which is why it’s important to start building a reel of your work as soon as possible. From films recorded on your phone to student films to indie shorts, examples of your work as a Director will help you get noticed and possibly hired for more substantial projects such as independent features, TV shows, and even multimillion-dollar movies.

How long does it take to become a Director?

The one thing about our game is that you need experience to get somewhere and no one’s gonna give you the experience.

I’m constantly astounded at how much I learn every day. Every single day I’m learning something new and something different because my attitude toward a script is, I look at the narrative, and then I figure out how to shoot it. I can now look at a scene or a schedule and begin to roughly sketch out how long it’s gonna take—and that’s through experience.

It’s a real oxymoron. I always say to kids, “Go out there and shoot, and shoot, and shoot, and shoot, and shoot, and keep shooting.” Even if it’s on a phone. Keep shooting, and watch stuff. Watch the DVDs of film, then watch the film. Listen to the commentary. Understand why people made decisions, why they went that way, why they went this way.

How do you balance staying true to your artistic vision while also meeting the expectations and demands of producers, studios, or other stakeholders?

Navigating the balance between art and business can be a challenging one. Ultimately, it comes down to a few factors…

- Articulating Your Artistic Vision

- Compromise

- Communication

- Flexibility

- Collaboration

As a director, having a vision for your project is crucial. What’s equally vital is being able to communicate that vision to a great number of people. Before you can explain your idea to your creative crew, you need to first sell it to investors, stakeholders, and producers. Expressing your movie in the most vivid and enticing way possible is necessary to get a movie made. Transparency will help align everyone and put them all on the same page.

The moment you start working with others, no matter what level, there is going to be compromise. This is a fact not only of the artistic process, but of life as well. Negotiation is a skill as valuable as communication, as different people will have different priorities and ideas on how things should be executed and produced. Sometimes you’ll need to be willing to compromise or sacrifice the less-vital aspects of your film in order to get it made.

This is an element that should be wide open early in the process of trying to get your movie made. Constant discussions and check-ins are necessary to ensure a continuous exchange of ideas and that no party is surprised by the actions of another. It’s extremely important that everyone listen to one another so as to move forward as one, unified production.

There’s a balance to be found between adhering to your artistic vision and being open to constructive criticism and feedback. You’ll want to hear everyone’s feedback and then decide which bits of information will prove the most beneficial and productive to your project.

Collaboration is where all group artistry lives. Ideally, all parties involved will share a common goal, which is to create a like-minded film and that’s when finding answers and solutions becomes a collective effort. This relies on commitment and respect from all ends, building a safe, creative environment where all ideas can get their due consideration.

Experience & Skills

A Director’s job encompasses far more than just directing the performances of the Actors.

Because Directors are generally considered the leader of a project, they must know how to interact with virtually every member of the crew.

Is it easy to become a Director? James Cameron lays out what you must do to find your place in this industry.

That means understanding to some degree the major facets of making a movie. The different skillsets of being a Film Director include knowledge of:

- Screenwriting

- Cinematography

- Production design

- Sound

- Editing

While a Director doesn’t necessarily have to be an expert in any of these specialties, they must know how to communicate their vision for the film to the people who are. In addition, as the go-to leader of a production, a Director must master these soft skills:

- Creating a cohesive vision for your project

- Managing the give-and-take of creative collaboration and compromise with other department heads

- Working within the budgetary confines set up by the Producer, production company, or studio

- Supporting the Actors through their creative process and getting the best performances out of them

This very unique skillset can be attained both with formal education and on-set experience.

What skills do Directors need?

You need to be able to listen. Your most powerful tools are empathy, and your ability to understand all sides of a situation so that you’re never judging anyone. When Actors are playing villains, the number one thing they say is: “You cannot judge your villain.” Your character is not a villain, because to them, they’re doing the right thing.

As a Director, you have to do the same thing. You cannot judge any of your characters. You cannot judge any of the crew or people that you work with. You have to be open and know when to decline something and know when it’s a good idea.

The more you shoot, the more you’ll understand those questions and how to answer them. Experience departments other than directing as much as you can, [both] above the line and below the line.

Try to edit. If you’re a good Editor, or at least someone who understands editing, that will be a really powerful tool to have as a Director. Not so you can take the mouse away from your Editor and go, “Let me do it,” but so that you’re able to communicate with them. Same with the DP. You wanna be able to talk with your DP as clearly as possible in their language.

When you’re watching movies and TV shows, study those things. Why are they editing it this way? What does that make me feel? How did everybody–the Director, Editor, Production Designer, etc.–make me feel that? Play it over and over again and figure it out. Dissect it.

The first thing you’ve got to have is an absolute cast iron work ethic. That’s really, really, really important. Especially if you’re a person of color, frankly, and if you’re a woman. You have to be undeniable, and that means really putting in the graft.

In prep, I tend to have maybe two hours, three hours consistently for about ten days because I’ve got to be ready for that first tech scout. So, work ethic is really important.

Being able to talk to people is even more important. Be tenacious, be prepared. [It’s] having a real bulletproof plan…and then being able to deviate with that.

Being able to course correct is really important. Being able to pivot is really important because things happen. The other day, we were shooting and we had rain and we also had kids, which meant I lost the kids at a certain time. I lost them because I had been rained out. I had to work on how to do the scene in less shots. Those are the sort of esoteric things.

But then the sort of practical: you have to know things like lenses, you have to know cameras, you have to know how to block. You have to know how to get out of a scene really quickly with the amount of time that you’ve got left, which seems an easy thing to do but it’s incredibly hard because you need coverage.

One of the things I’ve done just in the last four years is operate camera — which means I can pick up the camera and just literally shoot. A lot of my favorite Directors like Zack Snyder, Tony Scott, and Ridley Scott all operate…and they do it for a reason. I can just go, “Okay, I’m the roller of this, and I’m gonna do this, do that, do that,” without getting cut.

It takes out a couple of levels of communication [and] that’s really gonna save you time. Time is the biggest factor in my job: juggling time, working out your time lengths, and sticking to a plan that allows you to deliver on that time.

I’ve found that I want to know everybody’s job so if I can do it, I can do it. So I know that when I get on the floor how the DP’s gonna light [and] I know how long that’s gonna take. I know what the first AD does, I know what the Grips do, and I know how long it takes for them to do their job.

That really helps because all the time I’m doing this continuous sort of math puzzle, where I know that if I’m after that shot, I’m gonna have to come around, which means lighting this way, and this way, and this way, which means this, this, and this, and all these different computations go into my mind. Then I work out how long it’s gonna take and based on that I make my decision if I’m gonna do it.

If I’m honest with you, I’ve made up decisions in prep a long time ago. I write an extensive shot list. I write it again and again and again…and I storyboard. It’s great to have a plan, but as Mike Tyson said, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face.”

Having a plan allows you to pivot. A lot of the time, my job is all about setting up this shot here, but knowing that I’m gonna have to go to that set there and do this and do that, so you’re always five or six steps ahead.

Good communication skills, patience and a will to deal with people in a diplomatic fashion is a necessary foundation for a Director. You really need to know yourself and what your point of view is–both of yourself in the world, your world view and values and how you apply that to your work and the stories you tell.

Equally important to the craft of directing is a solid understanding of story, story structure, visual storytelling, knowledge of each department that you work with, “knowing your way around a set” is immensely useful. So, I think it’s great to try out working in different positions as you work towards your goal as a Director.

And, above all, being kind to everyone you work and being a good leader is vital. If you can create a positive environment for everyone to do their best work, and inspire them to do so, then you are more likely to be called back to work for more jobs.

I think the best Directors are wonderful communicators. You have an idea; it starts with a script, a story, and the Director is going to interpret that story to make it into a film or television episode. To do that, the Director must be able to communicate his or her ideas to his team and to the Actors.

Communication is essential, and the other thing is, I think, collaboration. You’re working with a team, and you want to bring the best out of the team so that you can tell the story you want to tell.

What do Film Directors do on a daily basis?

A Film Director’s daily duties will vary, based on where they’re at in the filmmaking process. A Director’s work will be very different during pre-production than it will be during pre-production.

Throughout the entire process of making a movie, a Film Director might do any of the following (in order from the start to finish of a film):

- Pitch potential film projects to investors

- Create pitch decks

- Weigh in on film casting, locations, and production/costume design

- Consult and run production meetings with department heads

- Help plan the shooting schedule

- Work with Actors to get their best performances

- Make sure the footage is working

- Call “action” and “cut” on various scenes

- Go through dailies for the Editor

- Work with Editor on picture lock

- Work with Composer on soundtrack

- Work with Colorist on the film’s look

- Do press for the finished film

- Accompany the film to festival appearances and red carpet premieres

- Repeat

Education & Training

A formal film education can play an important role in giving an aspiring Director early momentum for their career.

Film school can teach aspiring Directors the technical skills required in this field, and as mentioned, offer opportunities for a Director to test them out by making student films. At film school, aspiring Directors can also begin to forge those all-important professional relationships that could prove helpful down the road.

Whether you’re a novice or veteran Director, it never hurts to learn new tips of the trade. Click into this video to learn more.

If going to college for film isn’t an option, aspiring Directors can still make connections with those who do. Often student Filmmakers will post notices about needing extra help – such as for Production Assistants – which can be a great way for an aspiring Director to start getting that on-set experience.

Those just starting out can also look to see if any local productions are in need of extra help. With enough time and connections made, an aspiring Director can work their way up to actually directing a film one day.

Is film school worth it for Directors?

With filmmaking through USC, that’s really how I discovered what filmmaking was, the blend of entrepreneurship and artistry, and getting an understanding of what the roles were that went into filmmaking. But what I would say is that for someone who already knows they want to be a filmmaker, and if they’re reading Careers In Film they probably already have an idea that they’re interested in that, I don’t think going to film school is a critical or essential step on your path to becoming a filmmaker.

Because at the end of the day, your degree in filmmaking means absolutely nothing. As a Writer-Director, the fact that I went to USC doesn’t make an Actor want to be in a movie. It doesn’t make an investor want to finance development of a script or production of a movie. Those things are honestly completely irrelevant. The only thing that can speak for that is yourself as your own advocate, and your work.

Definitely. For me, yes. You know, there are people like Quentin Tarantino that didn’t go to film school. They worked in a video store. You don’t need to go to film school to become a Director. In fact, people come from different parts of life/jobs.

I went to film school because it afforded me the opportunity to have access to equipment and film. Also, I knew it would give me an opportunity to network, to meet other filmmakers and learn from other filmmakers.

I had three different experiences with film school. I went to Columbia University, initially. I was going there because I wanted to get medical school requirements, too, because I was thinking of being a Doctor. But I always loved film, so in my freshman and sophomore year, I kept taking courses at the graduate school—film history and film theory—because they didn’t have an undergraduate program then for film.

There was a limit [and] I got to the limit before you have to take production, but because I was an undergrad, I couldn’t do it. But I really got a great sense of European film, language, and theory because Miloš Forman ran the department at that time.

After two years at Columbia, I thought, “Well, I really wanna dive into film. I can’t go any further here.” So I transferred to USC, and from day one, (I went in as a junior) it was all production. I did every position you can think of and I networked, and I still have friends from that period—Academy Award winners and TV people—and after I finished there I thought, “Okay, I now want to really focus on directing,” and so I applied and got into the American Film Institute.

So I went to the AFI. The AFI was completely different; it was all about story. Story, story story. There wasn’t a class that taught you how to use a camera. There wasn’t any of that stuff. You go out, you’re making three short films, and you’re on your own. You use your classmates as your crew and we had access to SAG Actors.

When I look back at it, it was the best balance. Yeah, it made me broke, but it was the theoretical approach to film as language and using and seeing film in a formalistic way, then USC, which was much more hands-on and commercial, and it was about working to make movies, and it was more Hollywood-oriented.

And then, going to the AFI where it was much more conservatory, about telling stories. “How do you focus on story, story, story?” informs your choices for casting, which informs your choices for where to put the camera, and so that training to me was great.

The scholastic approach might work. It’s all very personal, you know? I’m not really that way. I kind of just want to get out there and make stuff.

Obviously, you can do that at college but I really feel there’s nothing quite like being in the cauldron of a floor, and working on a floor, and working with people on the floor and getting sweaty with people on the floor.

At the end of the day, when you’ve made your day, that feeling is incredible. To consistently go in every day–it’s something that happens to you that you don’t get anywhere else. So, if you’re asking me personally, I would say get on the floor and get on the job.

If you’ve got a contact in the game, it’ll get you on the floor. I would much rather be on the floor because you’re learning practically [and] it’s all about connections. The crews at this level are amazing. You cannot operate at this level if you’re an asshole. Right?

At this level, when you’re on the floor, everybody is so good at their job, and they’re really good human beings because all the bad apples have been weeded out, which tells you a lot about how the industry works. It’s a people thing.

Most jobs are all about someone calling you up and saying, “Oh, hey. Are you free?” and they’re going to go, “Yeah, I’m free,” and so developing that network is really important with Producers.

Let’s say you’re in camera. So if an Operator gets a job, he brings his agency, he brings his Loader, he brings everybody with him. This is a people industry.

The reason why I really recommend the floor route rather than the scholastic route is because people don’t know who you are until you’re on the floor under pressure. People can meet me, and they can like me, and then go, “He’s a really good guy.” But really canny people go, “Yeah, he’s a nice guy, but we’re in LA (or we’re in Toronto) and it’s a nice day now. But what’s he like when we’re losing light and we’ve only got an hour to do four shots? Who is he then?”

That is the real key; if people know what the answer to that is, they’re gonna hire you. If they know when the shit goes down you’re really cool, when things are really going wrong you’re incredibly disciplined [and] you don’t shout, they are gonna hire you and you can deliver.

That’s how you get referrals and that’s how people can hire you again and again—because they know that you’ve been tested and you’ve come through it.

I would always recommend going the floor route because you’ll learn. If you really, truly want to direct, you will learn.

Anything else you want aspiring Directors to know about?

First, you have to embrace who you are. Find your voice.

I know aspiring Directors say, “Well, I need an Agent,” or “I need to do a movie so that people will notice me. Oh, I need to write a script.” Scale back. Go back. Look within, and be true to yourself. Who are you? What stories do you want to tell? What story do you need to tell?

I approach that even in episodic directing of television because in episodic directing, you’ll get hired on a show and you’re handed a script that you didn’t write and it just landed on you because of the scheduling. What you have to do is go through that script and find the point of view. How can I elevate this material because of who I am?

That’s also knowing that you can’t change the show. You have to work within the established parameters stylistically and tonally that the show has created. So if you’re gonna go to CSI, you can’t go in there and shoot it like NYPD Blue, you know? It has to still be CSI.

But you can tell the story. Obviously, you’ll study all the episodes beforehand and see how they do it. But there’s still part of you that you put up there. I know very accomplished TV Directors and I just see it, and not knowing that they did it [the episode], I could say, “Wow, that looks like so-and-so’s work.” It’s because one tells a story based on who they are.

The other thing is that I heard someone once advise, “You don’t have to move to Hollywood. You don’t have to move to New York to become a Director. You can become a Director wherever you are.” People come to you if you’re telling good stories.

Keep asking “why”. Always be asking “why” and “how” because the moment you stop asking those questions is the moment you stop growing. You stop being curious, and therefore, you’re outdating yourself. You’ve put an expiration date on yourself.

Who is a famous Film Director?

Though cinema is little more than 100 years old, many famous Film Directors have emerged through this artform. Over the course of its history, it has produced notables such as Orson Welles, Alfred Hitchcock, Billy Wilder, Akira Kurosawa, Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, Spike Lee, Kathryn Bigelow, James Cameron, Ridley Scott, John Carpenter, and Jordan Peele… Just to name a few! Among the most famous Film Directors, likely most people are familiar with Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg.

What degree do Film Directors need?

In short, no degree at all. Many specialties in filmmaking do not require any kind of formal education, so long as you can demonstrate your skills through your previous work and referrals. That being said, many aspiring Film Directors choose to go to film school because it can provide a solid educational base for their careers, as well as opportunities to network and practice through student films.

Fun Facts

Current number of U.S. colleges and universities that offer a film major: 264.

Current number of DGA members: 19,500 (including other members of the directorial team such the Unit Production Manager, 1st Assistant Director, and 2nd Assistant Director).

Women who have won the Academy Award for Best Director: Kathryn Bigelow for The Hurt Locker (2008), Chloé Zhao for Nomadland (2020) and Jane Campion for The Power of the Dog (2021).

What is the hardest job in film?

No job in film is easy. That being said, many consider the position of the Film Director to be one of the most demanding roles because of the many requirements of this professions. Film Directors must be knowledgeable about virtually every aspect of filmmaking to be able to communicate with every department head, as well as keep tabs on every aspect of their project both in front of and behind the camera.

Who are the most influential film directors of all time?

So many directors have left indelible marks on the cinematic landscape, there may be too many to list. These visionaries have not only built compelling narratives but have also pushed the boundaries of the medium, redefining what’s possible within it. Let’s take a look at a few…

- Orson Welles

- Alfred Hitchcock

- Stanley Kubrick

- Martin Scorcese

Orson Welles’ debut film has landed in the number one spot (or in the top 5) of nearly every “best film” list ever created. CITIZEN KANE was a remarkable achievement, and in addition to its technical cutting-edge techniques and fresh approach to moviemaking, it’s also a monument to acting and writing.

Hailed as the “Master of Suspense,” Sir Alfred Hitchcock practically reinvented the device of tension in movies. Enduring classics like REAR WINDOW, VERTIGO, and PSYCHO showed that thrillers were no longer b-level fodder, but rather masterclasses in how to orchestrate a suspenseful piece of art.

Here’s his most famous scene, from his most famous film, PSYCHO.

There are few auteurs who have garnered as much respect as Stanley Kubrick has. A meticulous craftsman with a super-keen eye for detail, Kubrick’s films feel more like immersive experiences than a time at the movies.

Watch this sequence from 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY to get a feel for the level the filmmaker operated on.

Ever since he burst onto the scene in the 1970s, Martin Scorcese’s films have had a resonating impact. His distinctive approach to storytelling, in-depth exploration of themes, and dedication to pushing the limits of cinematic expression has put him at the forefront of ever-imitated directors.

Check out this steadicam shot from Scorcese’s masterful GOODFELLAS, where the film’s lead character (Ray Liotta) brings his girlfriend into the bowels of the Copacabana.

FAQ

Is it hard to become a Director? (additional info)

It is. It’s a lot of competition. A lot of people want to be Directors. In fact, a lot of people go to film school, and they say they’re going because they want to be a Director, and then, ultimately, in film school, they practice another position, and they realize, “Wow! What I really like is editing,” or “I really like cinematography,” or “I really like costumes,” you know? They end up branching out.

But it is tough to be a Director, not only because of the competition and so many people want to do it, but it’s how do we get to that professional grade? You can be a Director and make little movies, and little YouTube things, and stuff—and you’re a Director. You’re telling stories.

But in terms of making a living as a Director, that’s where it becomes tough because there’s a lot of competition, and also you’re only as good as your last film. So if your last film or TV episode wasn’t good, it’s harder to get that next chance.

So a Director’s constantly proving himself because you could have directed 110 episodes and if your 111th is not good, they’ll remember you for that 111th. They won’t remember you for the 110 that you did that were great. I had a famous Producer once tell me, “When you make it, know that staying up there is tougher than making it.” I tend to think both are tough: getting that first opportunity, and then branching out and continuing.

Yes, it can be. But if you love it, then it should mostly be fun. As the saying goes, there is no gain without a little pain. It’s a big life decision and I think that a part of the conversation about being a Director, or in the entertainment business in general, is that it is as much a lifestyle as much as it is a career.

You will work very long hours (easily 12 hours a day much of the time), sometimes for weeks, if not months on end, often away from home and family. It can be very trying on a relationship unless your significant other is also in the business, or is a very patient, supportive, understanding person. Once you get past that or, when you’re young and working towards your goal, it’s a lot of hard work, but really fun.

How do you become a Director? (additional info)

There are so many different paths to becoming a Director. You may have started in another position. For example, I know Script Supervisors who have become Directors, I know Cinematographers who’ve become Directors, I know Assistant Directors who have become Directors, I know Actors who have become Directors.

My journey [is that] I always wanted to be a Director, I started by writing a short film and I directed the short film. I screened that film, I put it in film festivals and that allowed me to get my first feature film. That got me my second film, and then on and on. That doesn’t happen often. I lucked out in many ways.

Another way is you write your own script. You write a script—feature or short film—and you go ahead and do it. Now, everyone’s able to do it; even with this little thing [referring to iPhone] you can make your own film. There’s no excuse for not telling a story if you want to tell a story. When I was coming up, we didn’t have these things.

One of the reasons I went to film school was because it afforded me the opportunity to have access to film cameras and film…and that allowed me to make film. But nowadays, anyone can grab a phone and make a film. Whole features have been made on an iPhone.

To be a Director, you have to be an observer of the world, of people, of the life around you. When you work on a story, you’re gonna tap into your sensibilities, into who you are to tell that story. That’s why if you see a movie, you’re seeing something that was created by somebody who has tapped into his or her life experience to tell that story.

So it’s important to be honest with oneself and to observe the world. When I was in film school and I needed to work, I was a Taxi Driver in New York City. I would carry a journal with me and any interesting person that I would meet, I would write it down. I kind of created a catalog of characters and people and I observed people because we ultimately, as storytellers, are telling human stories.

We need to tap into humanity. We need to have a connection with people, characters, locations, settings, history, and art. I think that’s an exciting thing if you approach it from that way.

There are many paths to becoming a Director. I became a Director because of my interest in visual storytelling. I read and drew comics as a kid and taught myself the basics of filmmaking before going to school to learn more. I concentrated on cinematography and worked in numerous other positions on the set at different times as well so that by the time it made sense to myself and to the people I worked with that I was capable of directing, I was offered the position.

I always considered myself capable of being a Director and loved making short films with my friends, so I was always headed in that direction.

I think it’s important to know what type of directing you want to do and what type of stories you want to tell, whether you write them yourself or not. The film and television business is very segmented into groups that make feature films, television, documentaries, commercials, and music videos.

Even within those groups, there are niches to consider: feature films have big budgets and low budgets, horror to sci-fi, comedy, etc., TV has big budget shows and also reality TV. There is crossover between those fields, but you have to work very hard to prove you are capable of doing a television show or movie if, for example, all you have done is music videos. It does happen and there are great examples of successful Directors that have made great leaps, but it is wise to keep a clear goal in mind.

Nobody knows. On the real though, I would say that how you become a Director is by doing it. That’s really the most annoying but accurate way to do it. It also makes it easier when you’re already doing it, which sounds strange because shouldn’t you already be doing it in order to get the job?

But it’s not necessarily that easy. When I say, “Just do it,” people think, “Oh, I don’t have money for a big camera and crew,” but that’s not what I’m talking about. We live in the age of technology; you can shoot anything on your phone, and you can cut it together and see what story it makes.

People are doing that every day on TikTok and Instagram. They’re Directors in their own right. They may be considered “content creators” nowadays, but they’re telling a story and making people feel something, and that’s what we do. If you’re finding opportunities to tell a quick story: beginning, middle, and end, in any way possible without getting paid, you’re directing.

That’s the other thing that people don’t understand. When you want to do something like this, a high-profile job, you’re gonna start with internships. You might not be getting paid to direct. If there’s a friend who’s got a script that you like, ask that friend if you can direct it. They’ll probably say, “Cool! Someone wants to shoot my thing? Yes, let’s do it!”

Just go ahead and do it that way. Keep making stuff, because people are gonna have a hard time hiring you if they don’t know what your eye looks like. When you shoot something, you’re telling us how your eyes see the world. If people are interested and gravitate and connect to what you’re saying, those are your people. “That’s your circus,” is what I say. Everybody’s crazy. The more we can be okay with that and embrace that, the more we understand. It’s just about finding your crazy.

That’s how you become a Director. I did this Rebel Without a Crew series. I hate plugging, but it’s really helpful. Robert [Rodriguez] has a book and a YouTube series. It’s like his own film school with all these behind-the-scenes tips on how to shoot stuff for cheap.

YouTube is a really great tool. I watch so many film critique channels like The Closer Look, Lessons from the Screenplay, Wisecrack, and StudioBinder. It’s basically free film school. Go do it. You don’t have to pay tuition. You don’t even need to pay the Masterclass fee. It’s all online now, so there’s no excuse. Take the desire of what you want to do and put it into action.

I sometimes spend hours watching [YouTube], and then I rewatch things later because something else clicks. When I’m in a different place in my life, when I’ve been thinking about different things, I’m gonna see something different.

I started The Water Phoenix in 2015, and it took a long time to finish. But when I was making it, nobody gave a shit about mermaids. (I’m sorry I cussed.) I thought, “Everybody’s obsessed with vampires and werewolves, and they just keep recycling that stuff.” So I said, “What if we did mermaids in that way instead? What if they were in our real world? What would that look like? How would we treat them?” So I was doing it for that reason.

Siren came two years later. At first, I was like, “Oh man, I have a mermaid short, guys!” It wasn’t finished at that time, but I said, “I have a mermaid short! Clearly I can do this. Hire me! Hire me!” but nobody cared. I did get to meet some of the execs at Freeform, but I was just too new for them to hire me at that moment, or even think of me and pass me on to the creators. But me having that short and me growing as a Director made it easier for them to hire me when they did, because they already knew me. They’d already met me, and then they’d seen me grow.

So then they thought, this is a no-brainer because she’s already done it. What’s funny is while I was on set, the lead (Eline, who plays the mermaid) was like, “You’re the first mermaid Director. You’re the first Director who’s actually done this, and I’m really excited about that.”

See? She was excited because I knew what it’s like to be underwater and to try to hold your breath, and try to look beautiful, and move well. That’s a very specific skill. Now I have that skillset, and it makes me valuable to shows that do underwater work.

That is a really, really, really, really difficult question. There are so many different paths you can take. I took the writing path. I joined the BBC and the BBC trained me. I started radio, then from radio, I graduated to TV, and I did documentaries, and then from documentaries I wanted to do more long form [projects], and I started to write scripts. I knew that the one thing I could do that no one else could give me permission for was to write.

That’s the first thing I would say to kids. If you can write–even if you can’t write–start doing it because it’s the one thing that you can do yourself. When I shoot something, I need 350 people to help me realize what I’m gonna shoot, right? It’s very hard to get that break.

But writing, you can just do. If you’re disciplined and you can kick out two pages a day — or five pages a day — and you can write a good script, you can get attention. And if you get attention, you’re in. So that’s one way to go in.

The other way to go in is to get a job in the crew and get a craftsman job–a Grip, a Gaffer, Electrician, Camera. If you get in any of those departments, you’re learning a real craft.

Say you manage to get a job as a Camera Trainee. It’s an incredibly brilliant job to get because it’s really hard work but you’ll learn a craft. Soon enough, you’re pulling focus, after three or four years. You get to work, and you get to work in the field. A lot of Directors have gone through that route. Barry Sonnenfeld started off in camera. He was a DP and then became a Director, so that’s another route.

The problem is a lot of kids when they get into that route, they’re making so much money — because you’re making $2,000 or $3,000 a week, even if you’re quite low down the ladder — and they’re so tired from the hours that we work that they forget that they need to film on weekends, or get together with some of the crew and film this short film.

That’s what tends to happen; a lot of people forget about their dream because they’re suddenly making money and they’re so tired. That’s why I talk about being tenacious and knowing exactly what you want. Continue to go for it.

The third route is through programs. Warner Bros. do an amazing scheme that I was on about ten years ago where they take young filmmakers and you do a twelve-week program with a woman called Bethany Rooney, who’s a wonderful Director. And after that, they guarantee you a TV job.

It’s very hard to get a TV job, but Warner Bros. do something, NBC do something. They’re very, very, very competitive, and they’re very, very, very difficult to get on. I know people that have tried for seven, eight years, and they haven’t got on. But, like I said, I got on and it changed my whole career because it made me accessible to TV. Now I do TV and film and I’m pretty fortunate to be able to do that.

I had what I have found to be kind of a non-traditional start in the film industry. I was lucky to get an academic scholarship to USC, and I came to study entrepreneurship. USC Film School is the institution that introduced me to filmmaking.

The biggest thing that I got from USC was an exposure to the idea that being a filmmaker was both being an artist and being an entrepreneur. That was so compelling to me because I had always felt like those were two aspects of my character. My dream was to find a career that allowed me to exercise both. I just didn’t really know before going to USC what that was because I was starting businesses, and that was cool, but it wasn’t really creatively satisfying.

I graduated from USC in 2014. I got there in 2011. (I ended up graduating in three years.) And I started working in the film industry, doing script coverage. I worked for a Lit Agent at ICF, who represented these amazing Directors like Antoine Fuqua, the Director of Training Day. I was like the first line of defense for all these screenplays that came in that were seeking directorial attachments. It gave me an appreciation for how difficult screenwriting was as a craft because if most of the screenplays I’m reading from established Screenwriters are bad, then it’s definitely not an easy thing to do well, you know?

I was continuing to work in making my first short films and developing my skillset as a filmmaker, making all the amateurish mistakes that a lot of my classmates at USC made when they were ten years old on their parents’ VHS camera. But as I was working in the industry, specifically in production, I was gaining really good experience as a Line Producer and as an AD. I was learning how to budget and schedule commercials, music videos, and short films, and at the same time, I was also editing everything that I was writing and directing.

One of the really big takeaways for me in the early part of my film journey was the importance of throwing myself into every aspect of filmmaking because at the outset, who else is going to do that stuff for you? You can’t use the excuse of “Oh, I never produce anything,” or “I’m not an Editor,” or whatever.

You can’t use that excuse to not continue creating and growing as a filmmaker. Especially at the beginning of your career, there’s so many sort of mistakes and trial lessons. You just have to make those mistakes and get through those early projects to get to a point where you have a fluency in the film language so that you can actually start communicating what you want to communicate through your short films.

With gaining experience budgeting and scheduling, that gave me the ability where I felt, “Okay, I’m definitely ready to make my first feature film.” It gave me the ability and the insight to understand how to design my first feature film in such a way that I could actually make it and design it in such a way that no one could prevent me from making it.

I had already written several other features, several television pilots. I had spent all this time going through the process of meeting with production companies who liked my screenplay. I had been a finalist for the Sundance Screenwriters Lab with that script. I made a proof of concept out of that script. It got me a lot of meetings, and there was interest, but there was always something that held it back. This was like a $1M to $1.5M movie, and what I realized was I’m just asking for too much for my first feature film.

As a Writer/Director, one of the biggest hurdles you’re gonna face is making your first feature. Until you’ve done it, you’re not really considered a real Director. But to do it, people need to believe that you can do it. But if you haven’t done it, why would they believe it?

So, there’s like this crazy catch-22, and what I realized was I just need to make my first movie…and if I have to do it with no budget, I’m gonna have to do it with no budget. If I have to wear a bunch of hats, even if I just wanna focus on the directing — which for me is the thing that I enjoy the most about filmmaking — then I’m gonna have to wear other hats, like I have throughout all these early years of just starting as a filmmaker.

The really critical thing for me was making the decision that no matter what the outcome was gonna be for this movie, I was ready to make my first feature film, and if it resulted in an embarrassing failure — which was such a possibility at all points throughout the process, and only increased exponentially when I decided, as we were casting that I had to play the lead role in the movie without any real acting experience before.

It was coming to terms with that risk and saying, “I am willing to risk that failure and that embarrassment because I know no matter what happens from a results standpoint with the movie, I will have directed my first feature film, and I will have learned everything that went into that, and I will be better positioned to make my next movie.” That was definitely the turning point for me as a filmmaker.

Sources

Hisham Abed

Hisham grew up on a staple of comic books and art which led to interests in animation and cinematography. He applied cinematic skills learned on indie features to redefine the reality genre on such shows as Laguna Beach and The Hills.

He has earned an Emerging Cinematographer’s Award from the International Cinematographer’s Guild and two Directors Guild of America nominations for work on The Hills and the ABC pilot Encore. His recent work on Queer Eye for Netflix has earned him one Emmy and a second nomination for Best Directing of a Structured Reality Program and has also earned him his third DGA Award nomination.

Norberto Barba

Norberto Barba is the Executive Producer/Director of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit. He also served as Executive Producer/Director for FBI, Mayans MC, Grimm, and Law & Order: Criminal Intent.

In addition to directing the pilots of Mayans MC and Lights Out, Barba has directed over 100 hours of television including Better Call Saul, Wu Tan Clan: An American Saga, Preacher, The Strain, The Path, S.W.A.T., Designated Survivor, Chicago Justice, Pure Genius, The Bridge, Lights Out, Ice, Against the Wall, Trauma, In Treatment, Fringe, The Event, Suits, NCIS: Los Angeles, Blade: The Series, Conviction, Threshold, CSI: Miami, Kojak, Medical Investigation, American Dreams, CSI: NY, The Mentalist, Numb3rs, and Resurrection Blvd.

His television movie credits include Family Channel’s Emmy-nominated Apollo 11: The Movie, Disaster at the Mall, and Lost in the Bermuda Triangle.

His first theatrical feature, Blue Tiger starred Virginia Madsen and Harry Dean Stanton and was followed by Sony’s Solo starring Mario Van Peebles and Adrian Brody.

Born and raised in the South Bronx to Cuban immigrants, Barba studied Comparative Literature at Columbia University for two years before transferring to USC’s School of Cinematic Arts to focus on film production. He then attended the American Film Institute as a Director fellow.

As a longtime member of the Directors Guild of America, Barba serves in the Creative Rights Committee and is a mentor in its outreach programs. He is also a member of the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (Emmy’s).

Barba is an alumnus of Rhinebeck, NY’s Camp Rising Sun and the prestigious Regis High School in Manhattan.

Barba served in a Psychological Operations Unit of the U.S. Army Special Forces.

Cassius Corrigan

One of the most exciting talents to break into the filmmaking scene over the last few years, rising Writer, Director, and Actor Cassius Corrigan is positioned to take the entertainment industry by storm.

Creating boundary-pushing stories that span genre and format, Cassius represents the next generation of multi-hyphenate filmmakers, bringing his passions for original storytelling, Latino-driven narratives and Mixed Martial Arts to life in film, television and documentary.

This year, Cassius makes his directorial debut with his critically acclaimed film Huracán. Praised by The New York Times as a gripping thriller they “couldn’t stop watching,” Huracán tells the story of an aspiring MMA fighter Alonso Santos (Cassius) who suffers from Dissociative Identity Disorder (aka Multiple Personality Disorder), which manifests itself in his aggressive and reckless “alter,” Huracán.

The film, which features a predominantly Latino cast, also stars Yara Martinez (Jane the Virgin), UFC superstar Jorge “Gamebred” Masvidal, Muay Thai world champion Grégory Choplin, actor/musician Steven Spence, and Colombian newcomer Camila

Rodríguez. Following a global festival run that culminated in an International Premiere at the 2020 Shanghai Film Festival, Huracán was acquired by HBO and became available on HBO and HBO Max on September 11, 2020.

Born and raised in Miami in a diverse family with Latino and Jewish roots, Cassius developed a global perspective that informs his filmmaking approach. He discovered the art of cinematic storytelling while on scholarship at the University of Southern California, graduating from its historic film school.

Cassius most recently wrapped production on the upcoming gangster film The Birthday Cake, which he Co-Produced and 1st AD’d. Directed by Jimmy Giannopoulos, the film stars Val Kilmer, Ewan McGregor, Luis Guzmán, and Penn Badgley, with Endeavor Content handling worldwide sales and targeting a Christmas 2020 release.

On the television front, Cassius was recently hand-picked by Brian Grazer and Ron Howard for their prestigious Imagine Impact program, designed to discover the filmmaking voices of the future. Through the program, Cassius has developed an original international MMA series set in Brazil, under the mentorship of Entourage creator Doug Ellin. He is also developing an original international music drama for eOne.

A passionate mixed martial artist who has created documentary content for Conor McGregor, Cassius is dedicated to creating breakthrough global content for the fast-growing sport of MMA, and to empowering Latino voices and stories through cinema. He currently splits his time between Los Angeles and Miami.

Photo credit: Galfry Puechavy

Bola Ogun

Bola Ogun is a first-generation Nigerian-American filmmaker whose directorial television debut was with Ava DuVernay’s Queen Sugar on OWN July 24th. She was previously selected for the class of 2014 AFI Directing Workshop for Women, the inaugural class for the Ryan Murphy’s Television HALF Mentorship Program, one of the five filmmakers for Robert Rodriguez’s docuseries ‘Rebel Without A Crew’ and a participant in WeForShe’s DirectHer program as well as Warner Brothers Directors’ Workshop where she secured an episode to CW’s LEGACIES.

Ogun’s second short film Are We Good Parents? had its world premiere at SXSW, took home 2nd Runner Up for Best Narrative Short at Urbanworld and won Best Short Film/Emerging Filmmaker at AT&T’s SHAPE Event. Her work has received positive reviews from Black Girl Nerds, Shadow and Act and was tapped by Essence Magazine as one of the 22 Black Directors Who Answered Hollywood’s Call For Diversity And Inclusion. She honed her strong filmmaking skills and knowledge by working in the production department for 8 years on notable projects such as The Dark Knight Rises, Neighbors, Battleship, True Detective, and Friday Night Lights. Which led her to produce the Emmy campaign music video for Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, Vanity Fair’s viral video “Ladyboss” and four Capital Records music videos.

In 2015, she penned a guest post for Indiewire titled “Enough with the ‘Black Movies’ Bring on the Black Mermaids,” an essay on bringing intersectionality to Fantasy and Sci-fi films. Her hope is to use her lens to influence those who don’t often have a voice and collaborate with other creative minds to amplify fresh storytelling perspectives.

Mark Tonderai

Known for his hands-on directing approach and undeniable eye for talent, British-Zimbabwean filmmaker and writer Mark Tonderai has become one of the most in-demand directors in the entertainment industry today. This year, Tonderai is set to direct Paramount Picture’s thriller-horror feature film, Spell.

The film stars Omari Hardwick (Power) as a man who crashes his plane while en route to rural Appalachia with his family and awakens to find himself completely alone and without his bearings. Relieved to be discovered by a seemingly kind elderly woman (Loretta Devine), he has no way of knowing the dark machinations that lie in wait as he is pulled deeper and deeper into a sinister world. Spell was released in select theaters and at-home on PVOD on October 30, 2020.

Tonderai made his directorial film debut in 2008 with the British psychological thriller

Hush (Optimum Releasing). The film, which Tonderai also penned, follows a young couple who are drawn into a game of cat and mouse with a truck driver, following a near accident. It was nominated for a British Independent Film Award.

Tonderai is perhaps best known for his work on the 2012 horror-mystery House at the End of the Street (Relativity Media) starring Jennifer Lawrence (Silver Linings Playbook) and Max Thieriot (Bates Motel). The film follows a mother-daughter duo seeking a fresh start in a town with a chilling secret and made over $66 million at the worldwide box-office.

On the television front, Tonderai continues to direct episodic series for major streamers and networks, including Netflix’s Locke and Key, Hulu’s Castle Rock, and Fox’s Gotham.

His directorial work on the BBC’s Doctor Who earned his episode the Visionary Arts Organisation Award for Television Show of the Year at the 2019 BAFTA in London. The season 11 episode, titled “Rosa,” centers around Rosa Parks and continues to hold a 97% rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

As a Writer, Tonderai co-wrote the 2001 British comedy Dog Eat Dog, starring Ricky Gervais (The Office) and David Oyelowo (Selma).

Born and raised in London and Harare to British and Zimbabwean parents, Tonderai started his career in media as a DJ host on BBC Radio 1. He transitioned into writing for television on ITV’s talk show Friday Night’s All Wright, and went on to create the BBC 2 sketch show Uncut Funk.

Tonderai currently resides in Los Angeles.