Short answer: Not a lot.

“Script” is a generic term that can refer to virtually any medium intended for a screen. That can mean a film, television show, web series, or even a TikTok video.

The term screenplay is usually reserved for a script intended to become a film, but many industry professionals also use it when describing a TV script. As it would imply, the term teleplay refers only to a script for television.

What are the 5 elements of a screenplay?

Regardless of genre or story specifics, a successful screenplay will generally have these five elements in common:

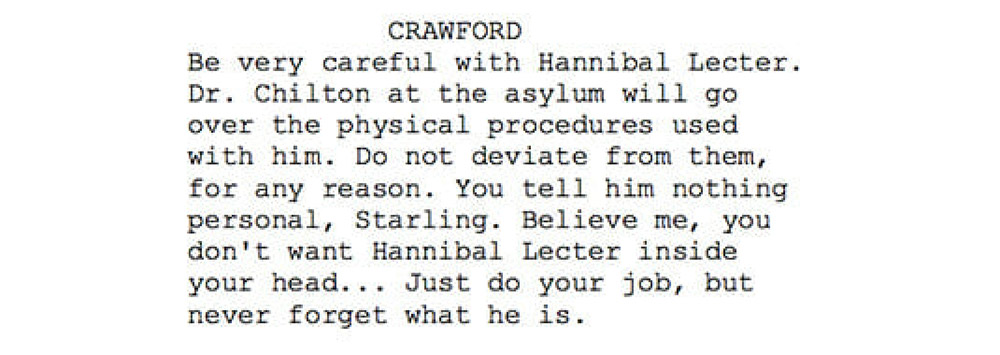

1. Interesting characters. Audiences want to cheer for a sympathetic protagonist and hate on a devious antagonist. They want compelling supporting characters who either help or hurt the protagonist’s chances of attaining their central want or need. In short, a great script will have interesting and dynamic characters.

2. Protagonist’s goal. But why are we following the protagonist for two hours or more? Spending that time just to watch them clean their house or run errands is not going to satisfy from a storytelling perspective. Instead, the protagonist must have a clear and compelling goal. To survive a shipwreck. To win back their high school sweetheart. To be the first woman on Mars. Make the goal one where there is a risk of failure. It should never be a sure thing.

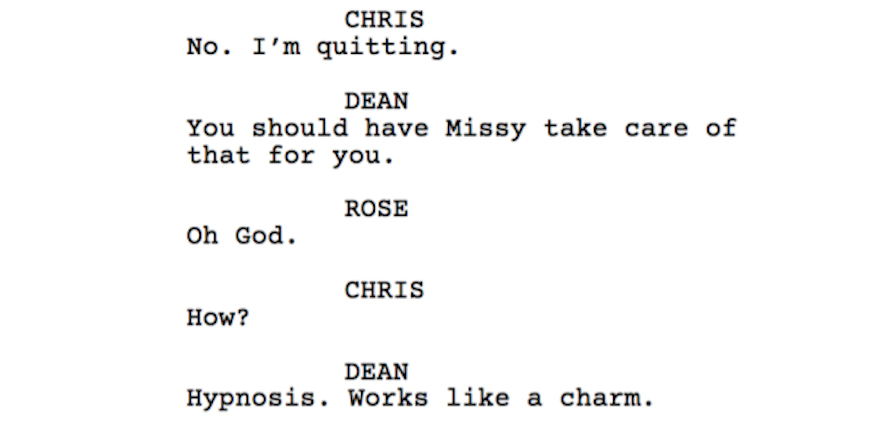

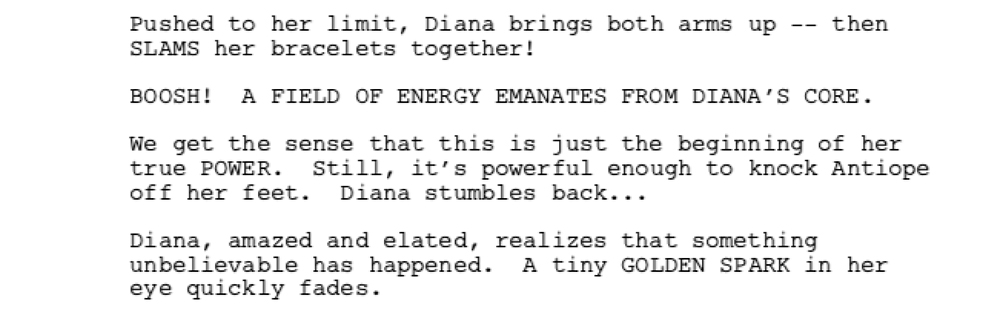

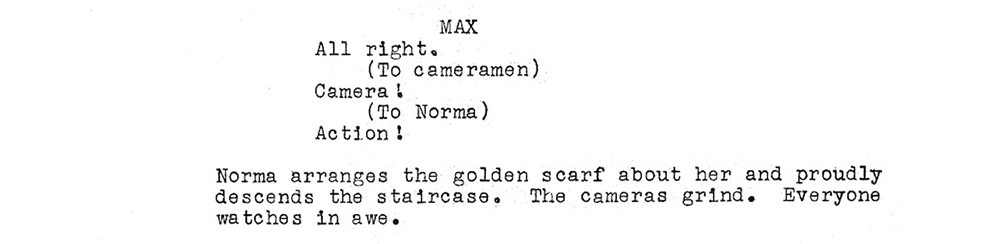

3. Compelling plot. What’s the story that will be told as the protagonist attempts to achieve their goal? Scripts are very much a show and not tell form of storytelling. Dialogue is a critical part of a screenplay, but you won’t have a compelling script if you just have the characters sitting around and talking about what they want. Give them stuff to do. Include plenty of action – even if it’s not an action movie!

4. Strong script structure. Feature scripts generally follow a three-act structure. The first act introduces the main characters, the stakes for the protagonist, and the inciting incident that sets them on their path to hopefully achieving their goal. The second act largely encompasses the highs and lows that the protagonist encounters as they move closer to or further away from their central want. Finally, the third act has the protagonist confront their final and most significant conflict – the climax – as well as the outcome to it.

To some degree, Screenwriters can tweak what happens in each act, but often the mark of a strong script is one that relies on having a solid three-act structure.

5. Conflict and resolution. It’s great if you love your characters. After all, you’ll likely be spending weeks if not months with them. But you have to make life difficult for them. A story where the protagonist immediately achieves their goal with no struggle or heartache isn’t much of a story at all. They need obstacles – and lots of them. That’s what makes ultimately the resolution where they do or don’t get their want so satisfying for audiences.