Film Career Finder

Start Here:

How to Become a Showrunner on a TV Series

Career Overview

Showrunners are in charge of the writing and execution of a television series. They run the Writers’ room, guide Directors and creative crew, and collaborate with the studio/network to deliver their unique vision of the show.

Alternate Titles

None

Avg. Salary

$100K to $300K an episode1

Salary Range

$30K an episode to $20M a year1

How To Become a Showrunner

- A Showrunner is the lead creative behind a TV series who oversees hiring, casting, writing, production, and post

- Most Showrunners come up through the Writers’ room, sometimes starting as an assistant, then staff writer, and beyond

- Network television Showrunners are one of the highest paid professionals in the TV industry, and can make anywhere between $30,000 and a couple million dollars per episode

- As Showrunners are heavily involved in every episode, the career of a Showrunner could be both creatively rewarding and mentally exhausting

- Key skills for aspiring Showrunners include writing, organization, leadership, emotional intelligence, and communication

- While no formal education path is required, it’s helpful to write a lot, read scripts, and develop a unique creative voice

- Career Description

- Salary

- Career Outlook

- Career Path

- Experience & Skills

- Education & Training

- How to Get Started

- Additional Resources

- Sources

- References

Career Description

A Showrunner is the person who leads the production of a television show. While the Showrunner is often also a Series Creator and/or Producer, their primary role is to lead the creative vision and oversee the writing team, including making major hiring, creative, and production-specific decisions.

Showrunners vs Producers

As mentioned, a Showrunner is often credited as a Producer, but the responsibilities of a Showrunner are much different from most Producers’ responsibilities. While the Showrunner could be seen as the overall creative director of the series that leads the writing team, Producers typically manage specific logistical areas of production, from budgeting to post.

What Do Showrunners Do?

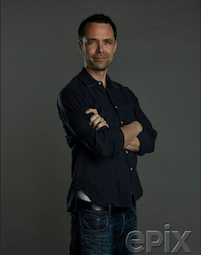

To figure out what exactly Showrunners do, we spoke with Davey Holmes, Creator and Showrunner of Get Shorty on Epix.

He explains the day to day responsibilities of a Showrunner: “Every day is different depending on the time of year. Before production starts, it’s a bit easier — I start the day a little later so I can get my own writing done, then go in and work with the Writers’ room, Script Analyst and Script Reader.

“We meet three times a week, so we have two days to do the actual writing. Around the writing, I’m crewing up, hiring people, and starting to do early casting. But largely, pre-production is all about breaking stories and writing scripts.”

Once they’re in production, Holmes illustrates just how much work there is beyond the writing of the scripts: “There are a bunch of skillsets that aren’t just common sense, different from what is required of you on a creative level, which is already hard enough. There’s a myriad of tasks that have nothing to do with the right side of your brain: organizational skills, management, all that stuff.”

Want the basics of what it means to be a Showrunner? This video does just that.

He goes on to illustrate the variety of daily jobs: “I’m always looking at casting tapes or approving costumes along with the Director. And there are always fires to put out. For example, an Actor might be having immigration problems getting into the country and we have to figure that out with our Legal Department. Or someone’s daughter is graduating, and they need to reschedule — we have to move the shoot around new dates.”

Interestingly, Holmes feels the writing is the hardest job, saying, “The other tasks? They are doable on their own, but you’re being pulled in so many different directions all day, it becomes challenging.”

Holmes goes into more depth, explaining what happens in his regular production meetings with the department heads: “We’ll go through the current episode on a technical level to make sure we’re all on the same page. Then I’ll have a ‘tone meeting’ with the Director, the Editor, the 1st AD and the DP.

“Tone is crucial — we go through the episode scene-by-scene for me to stress what I think is important, or ideas or staging that might not be clear. No matter how clear I think I’ve been, I’m always amazed at the miscommunication that can happen in terms of the direction of a scene. That’s what the tone meeting is all about.”

Holmes is clear that the Writers’ room is where the magic really starts, and he lays out the process in there: “We break scripts together, then the Writer gets a couple of passes, then we all do notes together. I like to note the scripts with the whole room; everybody weighs in and we work for a while on them.

“After that, I take the script for the final pass. That’s usually a fairly intense pass in this show, even on my own stuff. I remind my Writers not to be distressed — even my own work goes through the grinder at the end!”

Showrunners also have tight relationships with the studio and network executives, listening to their notes and liaising frequently from outline to script.

Says Holmes, “I have a very good relationship with all of them. I respect their opinions and vice versa. I don’t have to take their notes, but I do take most of them because they tend to be helpful. Sometimes the notes won’t make sense right away, but days later I’ll see the note was helpful. I’ve never had to take a note that I couldn’t get my head around.”

Salary

The average salary for established TV Showrunners is between $100,000 and $300,000 an episode. The salary range for first-time Showrunners is more in the range of $30,000 an episode. Then you have salaries of $20 million a year for Shonda Rhimes-level Showrunners. She is certainly on the high end of the most handsomely paid Showrunners in the world, as she currently has a $150 million contract with Netflix.

If you’re not working, you’re not earning, just like any other job in the entertainment industry. Of course, Showrunners are almost always Executive Producers on their television projects and that means they earn back-end from the continuous airing and distribution of their shows.

On top of their Producers’ fees, they are also paid as Writers on the show, so even if there are periods in the year when they are dark, the earnings are still extremely healthy to see them through.

Career Outlook

Holmes sheds some light on the most difficult part of showrunning: “Work/life balance is really tough, but I am getting better as I go. Honestly, you make a trade-off with how much of an auteur you want to be, how much you want to exercise creative control over every detail, and how much you have left over for your life.

“When we go into production, I do go into mourning for the friends and family I’m not seeing throughout the year. Season 1 we shot in Albuquerque and L.A., Season 2 in L.A., and Vancouver in Season 3. I’m all over the place!”

Being a Showrunner for a streaming service like Netflix is not the same as being one for a network show. These Showrunners break down why.

Time off for Showrunners is rare to come by: “I don’t really get a hiatus, it’s almost laughable. I’m in every cut, every color timing, every mix, and by the time we’ve done the last sound mix, it’s just about time to open up the Writers’ room for the next season.

It’s a point in the year when I have to look inward and come to terms with the desperation I feel when I have to set back up the day after we just finished.”

To a certain extent, it’s an issue exacerbated by Holmes’ attention to detail: “Sound mixes, for me, are huge. Everything’s dark by then and the show’s wrapped up, but it’s a really important, unseen part of the show for me. People do delegate that stuff, but I don’t know how to do that.”

Career Path

So, how exactly do you become a Showrunner in television? To reach the ladder-topping level of Showrunner, you will have risen all the way through the industry. Holmes clarifies, “Most Showrunners come through the writing room. There are other ways — through writing novels, for example — but the successful ones almost always rise through the Writers’ room.”

Anyone looking one day to run their own show can take heart from Holmes’ own story. He was once a convicted felon and also played for the band The Mighty Mighty Bosstones.

“Everybody has their own story about what attracts them to this world. In my own case, I became a Playwright. I was bartending for years in New York and finally got some traction with a stage play. That bagged me a real agency, got me noticed, but even then it still took a couple of years to get a television job — I had to figure out what I wanted to do.”

Want an insider’s perspective on the professional life of a Showrunner? These hugely success creatives talk about their roles on their respective series.

Showrunners are almost exclusively products of Writers’ rooms so any experience writing on a show is essential. As far as entry-level writing jobs, it is challenging but Holmes has a suggestion: “It’s never easy at the start, which is why I recommend just writing. That way, when you have a solid script, people will take notice and you can step into any Writers’ room.”

He remembers his own experiences at the start of his showrunning journey:

“About a decade ago, I was trying to hire Writers for a pilot of mine. Nowadays, when I look at the junior Writers I wanted to hire back then, they’re all running shows because they’re good. I remember calling their Agents back then, expecting them to be incredibly grateful for the call, but the attitude I got was actually, ‘Well, get in line!’ So if you have a fantastic script, the work really is done.”

Some career tips from Holmes on how to become a Showrunner in television:

- Write A LOT. All those terrible scripts at the beginning are part of finding your voice, and honing it.

- Read scripts A LOT. You can learn a lot from other people’s work. You’ll begin to understand what works, what doesn’t, and why.

- Stay loyal to what you really love to say.

Experience & Skills

“Showrunning is different from writing,” says Holmes. If you want to eventually run a show, it can be useful to start working on skills that are not instinctive to many Writers:

“The management side is a whole different skill set. Most Writers don’t work on their management and organizational skills. Many are eccentrics or solitary and none of that lends itself to managing 200 people. I am fairly decent at that now, but I have had to learn to be more organized, more punctual — all things I was not inherently keyed into before I came to this job.”

In terms of real education and training, Holmes is more interested in people finding their own voice. If that means going to college to study philosophy, or working as a Carpenter, or nursing, or laboring, so be it.

The essential craft is built through hours of writing, then letting it fly. Holmes has some practical advice for young Writers: “Be ruthless about getting your stuff out there. The good news is, the industry needs new voices, new talent, and new material. Your voice needs to separate you from everyone else who wants to be considered. You have to be forthright and proactive about getting reads.”

You now know what it is, but how do you do it? Learn how to get your foot in the door to eventually becoming a Showrunner.

Holmes is pragmatic about how “getting read”’ actually works: “Of course, some projects are easier to get on than others. I wanted to write on The Sopranos when I started but I wasn’t experienced enough for David Chase. Even with Get Shorty, I’m not really looking for first-time Writers, but there are Producers out there scouting at the lower levels and they will respond to smart stuff.” The conclusion here is: Write. A lot. Then get it out there.

Holmes is crystal clear about the important personality work anyone must do if they want to be the leader on a television series:

“Really, it’s about proper self-assessment. You have to know your strengths and weaknesses. With me, I get very emotional, and I can have a temper. I agonize over work and stuff ends up not getting done (creatively). Those are all things I have to counteract consciously.”

Holmes is clear that there is no one personality that succeeds in showrunning — everyone is completely different, and that brings color to the world.

He explains, “For me, both sides of my brain are fairly functional, and I enjoy the organizational side a lot. I’m able to wear both those hats. Conversely, others like to bring in people to fill roles at which they would otherwise be weaker. You have to know yourself, then just watch people who are doing a good job at this.

“It’s an incredibility challenging thing, even though we’re not saving lives! I worked under John Wells who did a beautiful job showrunning and I learned a lot from him.”

It’s equally important to learn from experiences that are less successful: “I did a million shows before Get Shorty,” says Holmes.

“I tried to pick the most interesting, strangest thing, but sometimes you get on board, and you realize it’s a turkey — you’re doing your job, but you know the ship is sinking. And that’s okay. I did a lot of unsuccessful projects that were still interesting in a lot of ways.”

Education & Training

Holmes is clear that finding your way into a Writers’ room is the first step, and that involves writing a lot of dreadful work: “I never did any screenwriting classes. I just wrote terrible stuff for years, over a dozen scripts that no one will ever see. I could hear rhythm, but I was so into rhythm, I didn’t care about story.

“When I finally learned how to tell a story (which you need to be able to do!), I had been practicing a different skill which made my voice different from others’.”

Knowing what a Showrunner does is key; knowing what they shouldn’t do is just as important, as Bruce Ferber explains.

Holmes remembers reading a ton of other people’s scripts and explains that he could “feel it” when he made a jump forward: “I knew I was ready to write something good — it happened with a play I wrote and the same thing happened in TV. I actually got a television job before I was very good at it, but when I was ready to write my own pilot, I could just feel it in my fingers and toes.”

Holmes is not a fan of screenwriting classes, but he is adamant that time and effort in the beginning eventually pays off. “Put in those ten zillion hours and it’s effort that no one can take away from you. And you develop your voice. Writers have an advantage over Actors and Directors — they have to get other people together to do the job — whereas we Writers can always go off, pound away, and make work.”

How to Get Started

- Get clear on what a showrunner actually does. A showrunner is the head writer plus the person making final calls across the whole series. That means story, tone, casting conversations, production choices, edits, and the politics of keeping everyone rowing in the same direction. Start by reading TV scripts and paying attention to how episodes are structured, then watch one season of a show you love and outline what happens in every episode. You are training your brain to think in seasons, not scenes, which is the showrunner muscle.

- Write constantly, but start small so you do not quit. Begin with short scenes, then build up to a full episode. Set a weekly target you can actually hit, like three pages a day or one scene a day. Try writing a spec episode of an existing show to practice matching voice and structure, then switch to an original pilot once you have some reps. The goal is not perfection. The goal is volume, feedback, and a clear improvement curve you can feel month to month.

- Make a tiny “proof of concept” so you learn production reality fast. Showrunners make creative decisions inside real constraints, so you need some time in the mess. Use your phone, a couple friends, and a location you can actually access. Shoot a two to five minute scene from your pilot or a short cold open. Edit it yourself. You will learn more from one scrappy shoot than a month of theory, especially about pacing, performance, and what is expensive on screen.

- Build a mini writers room, even if it is just three people on Zoom. Showrunning is a team sport. Find two or three reliable people who will trade pages, do table reads, and give notes that are honest but not cruel. Practice pitching story ideas out loud and taking notes like you are running the room. Rotate who “drives” the session so you learn how it feels to lead without bulldozing people. This is where you start developing taste and leadership at the same time.

- Learn the producer side: budgets, schedules, and how decisions ripple. Great showrunners understand money and time, even if they pretend not to. Learn the basics of a script breakdown, a one line schedule, and what costs explode quickly (company moves, night shoots, big crowd scenes, complex stunts). When you write, practice writing two versions of the same scene: the dream version and the smart version. Being able to protect the story while adapting to reality is what separates “writer” from “showrunner.”

- Get your first set gigs, any way you can, and treat them like film school. Look for PA work, internships, or office runner jobs on local shoots, student productions, commercials, or corporate video crews. The pay might be modest, but the education is real. Show up early, stay useful, and ask smart questions at the right time. You are learning how departments work, how problems get solved, and what professionalism looks like when the day is falling apart. Those lessons matter when you are the person in charge later.

- Aim for assistant roles that put you near writers and decision makers. If you can land work as a writers assistant, script coordinator, or showrunner assistant, you will see how stories are broken, how notes get handled, and how rewrites actually happen. If you are not in a major market, look for similar “close to the story” roles on smaller series, digital studios, local TV, or indie production companies. The point is proximity to the work and the people who do it, not the fanciest logo on the call sheet.

- Create a pitch package that makes your show feel real. Build a clean set of materials: logline, one page series overview, character bios, season one arc, and a pilot script. Add a simple lookbook with reference images and tone notes if you can. Keep it sharp and readable, not a novel. A pitch package is not about showing how much you wrote. It is about showing that you can run a coherent show for multiple episodes and make choices with confidence.

- Start getting paid by “showrunning” smaller projects locally. At the local level, showrunning often looks like leading a short-form series, a branded narrative project, a web series, or a pilot for a regional studio or creator. Pitch local businesses, nonprofits, and agencies on a small episodic concept where you handle writing, planning, and production leadership. Charge a flat project fee or a weekly rate. Even one paid mini series where you ran the whole thing is proof you can lead, deliver, and finish, which is what people hire showrunners for.

Additional Resources

Holmes notes, “[The] WGA ( The Writers’ Guild of America ) is the gold standard for anyone coming up in the writing world and it’s really worth checking out their website for networking events and advice on how to become a member in the first place. Again, it’s not easy at the start, so if union membership is something you see in the future, best to start writing now.”

Writers can also look to any number of film and television-centric organizations such as Film Independent or Women in Film for opportunities to network and learn more about the craft of television writing through their multiple professional programs.

Sources

Davey Holmes

Davey Holmes is a Creator and Executive Producer. His work for television has earned him a Writers Guild of America Award for Best Screenplay – New Series for In Treatment, and a separate Writers Guild of America Award nomination – Best Screenplay for Damages.

Holmes was born in Brookline, Mass. He became a delinquent youth and was a convicted felon, and dropped out of school to become a rocker with the Mighty Mighty Bosstones. He eventually graduated college with honors. He admits that one of his prior jobs was being the worst Cab Driver ever.

Holmes has had his plays performed in New York, London and L.A. Holmes has been writing for TV ever since.

The highlights of his television credits include: Get Shorty (MGM/Epix) – Created By, Executive Producer – 2017 to 2019; Shameless (Showtime) – Executive Producer, Writer – 2012 to 2016; Boomerang (FOX pilot) – Executive Producer, Writer – 2013; Awake (NBC) – Co-Executive Producer, Writer – 2012; The Chicago Code (FOX) – Supervising Producer, Writer – 2011; Happy Town (ABC) – Supervising Producer, Writer – 2010; Pushing Daisies (ABC) – Producer, Writer – 2009; In Treatment (HBO) – Writer – 2008; Damages (FX) – Writer – 2007; 3 LBS (CBS) – Co-producer, Writer – 2006 and Law & Order (NBC) – Writer – 2004, 2005.

His work as a Showrunner has been mentioned in Vice, Deadline, Variety, Consequence of Sound, Reel Talker, and Entertainment Weekly.

References

- 1THR Staff. "Hollywood's Salary Report 2017: Movie Stars to Makeup Artists to Boom Operators". The Hollywood Reporter. published: September 28, 2017. retrieved on: April 9, 2020